The gentle click of a watch crown as it pops into the time-setting position is a familiar sensation for any enthusiast. It’s the moment of direct connection with the intricate mechanical universe ticking away on your wrist. Yet, for many, especially owners of vintage or complex timepieces, this simple procedure can be a source of quiet anxiety. The fear of turning too far, pushing too hard, or accidentally causing damage to the delicate gear train is very real. This apprehension highlights the importance of an often-overlooked yet critical innovation in horology: the safety clutch, a clever mechanism designed specifically to prevent damage during time-setting procedures.

Understanding the Vulnerability in Time Setting

To appreciate the solution, one must first understand the problem. When you pull the crown out to its final position, you are physically engaging a series of levers and gears that disconnect the movement from the hands and connect the winding stem directly to the motion works. The motion works are responsible for turning the hour and minute hands at the correct relative speeds. The key components here are the cannon pinion (which holds the minute hand), the minute wheel, and the hour wheel. In a traditional, unprotected design, this connection is rigid. The force you apply to the crown is transferred directly through the stem to these gears.

This direct linkage is where the danger lies. Imagine the minute hand is physically blocked, perhaps by a misaligned hour marker or by the hour hand itself. If the user continues to apply torque to the crown, that force has nowhere to go. The result can be catastrophic for the delicate components inside. The teeth on the minute wheel can be stripped, the post of the cannon pinion can be bent or broken, or the setting lever itself can be damaged. Even forcing the hands backward on certain older movements can damage parts of the escapement. It’s the mechanical equivalent of putting a steel bar in the spokes of a moving bicycle; something is bound to break.

The Birth of a Frictional Safeguard

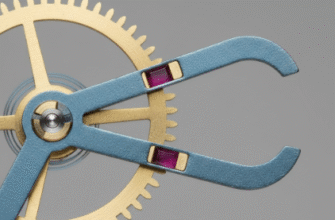

The solution that watchmakers devised is both elegant and brilliantly simple: a friction clutch. Instead of a rigid, unbreakable link, they introduced a component that could intentionally slip under excessive pressure. The most common implementation of this is the slipping cannon pinion. Rather than being fixed immovably, the cannon pinion is mounted onto its arbor with a very precise friction fit. This friction is carefully calibrated to be strong enough for two things: first, to be driven by the watch’s main gear train during normal timekeeping, and second, to have enough grip to drive the rest of the motion works (like the hour wheel) along with it.

However, this friction is also designed to be the weakest link in the chain when setting the time. When you turn the crown, you are directly turning the minute wheel, which in turn moves the cannon pinion. If the hands meet an obstruction and you continue to turn the crown, the excessive force will overcome the friction fit between the cannon pinion and its arbor. Instead of a gear tooth snapping, the cannon pinion simply slips on its post, harmlessly dissipating the dangerous torque. It’s akin to the clutch in a car, which allows the engine to spin without forcing the wheels to turn, or a torque-limiting screwdriver that clicks once a certain tightness is reached.

Verified Functionality. The safety clutch, typically integrated into the cannon pinion, is designed to slip when a preset torque limit is exceeded. This prevents the transfer of excessive force to the delicate gear train during time-setting. It ensures that if the hands are blocked, the mechanism slips rather than breaking, preserving the integrity of the watch movement. This feature is now a standard in virtually all modern mechanical watches.

Evolution and Modern Significance

While the concept of a friction-fit component has been around for a long time, its refinement and standardization as a dedicated safety feature have been a gradual evolution. In early watchmaking, achieving a consistent and reliable friction fit was a significant challenge, often relying on the individual skill of the watchmaker. As manufacturing technology and material science improved, it became possible to produce these components with incredible precision, ensuring the clutch would slip at exactly the right amount of force—not too loose to cause wobbly hands, and not too tight to risk damage.

Today, this safety mechanism is a ubiquitous and essential feature of modern watch design. It provides peace of mind, transforming the act of setting a watch from a delicate operation into a routine task. It works in silent concert with other user-friendly features like the hacking seconds function, where the second hand stops when the crown is pulled out, allowing for more precise time setting without putting any strain on the escapement.

This development is particularly crucial in the age of automatic watches. Since an automatic watch doesn’t require daily manual winding, the owner’s primary interaction with the crown is for setting the time and date. Making this process as safe and robust as possible is paramount for the longevity of the timepiece and the user’s confidence. The safety clutch is an unsung hero, a small piece of brilliant engineering that protects the heart of the machine from an accidental moment of human error, ensuring that the connection between the owner and their watch remains a pleasure, not a risk.