This request asks me to write an article that is over 5000 characters long, follow specific markup rules, avoid AI-like writing, and strictly adhere to all instructions, including Google AdSense rules (specifically avoiding YMYL content). The topic is the historical connection between watches and early underwater photography.To ensure the text is unique and avoids sounding like typical AI-generated content, I will focus on historical narrative, specific details, and evocative language, adopting a more journalistic or historical essay style.The topic, The historical connection between watches and early underwater photography, falls outside of the YMYL (Your Money or Your Life) categories (Finance, Health, Legal, etc.). It’s a general interest/hobby/history topic, so it complies with the AdSense rule.I must use the following tags: p, strong, h2, h3, ul, li, and a blockquote with either class check or warning. I must not include the title at the start, nor the body tag. The result must be only the code.Given the length requirement (5000+ characters), I will structure the article with distinct historical sections.(Self-Correction/Internal Monologue on Length and Content Strategy): To hit 5000 characters, I need about 800-900 words. This will require depth on the pioneers, the technical challenges, and the specific role of timing/watches. I’ll cover figures like Boutan, Williamson, and the evolution from dive bells to SCUBA, linking each step to the need for reliable timekeeping.Drafting Content & Applying ConstraintsPioneers: Louis Boutan (first true underwater photos), John Ernest Williamson (photography from a submersible), Hans Hass (early SCUBA and photography).Technical Link: Timing (exposure, gas consumption, decompression stops). The need for a waterproof and reliable timepiece was immediate.Watch Evolution: From basic pocket watches in pressure-proof cases to purpose-built dive watches (pre-Rolex/Omega era, focusing on the idea of a waterproof watch).(The following is the output as requested.)

The dark, mysterious world beneath the waves has always captivated the human imagination. Yet, for centuries, it remained an inaccessible realm, its secrets guarded by pressure and lack of light. The quest to both explore and visually document this silent world gave rise to two remarkable technological fields: **underwater photography** and the development of the **waterproof timepiece**. Their historical connection is not merely coincidental; it is a profound story of mutual necessity, forged in the depths where a minute could mean the difference between a successful image and disaster, or even life and death.

Before the advent of self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA), early pioneers relied on cumbersome diving bells, heavy standard gear, or limited breath-hold dives. The first true efforts at underwater photography in the late 19th century were inherently limited by these mechanical constraints, but the biggest technical hurdle was **time**. Specifically, the need to precisely control long exposure times in the dim underwater environment and, crucially, to track the limited duration of a diver’s time at depth.

Louis Boutan and the Dawn of Aquatic Timekeeping

The story begins most definitively with **Louis Boutan**, a French zoologist. In 1893, in the Mediterranean waters near Banyuls-sur-Mer, Boutan succeeded in capturing the first clear underwater photograph. His challenges were immense. He had to create a bespoke, pressure-proof housing for a standard camera, but perhaps his most critical innovation involved light and time. Because natural light diminished rapidly underwater, he initially required exposures as long as 30 minutes, an eternity in the cold, dangerous depths.

The development of an underwater flash system—first using an oxygen-fueled lamp and later a chemically ignited magnesium powder—drastically reduced exposure times. However, the reliance on a diving tender and the inherent danger of working under pressure meant that the diver’s absolute time spent submerged had to be meticulously tracked. This was the moment the **reliable, sealed watch** transitioned from a convenience to a critical piece of safety equipment. The diver or their tender needed a robust timepiece that could withstand the damp, corrosive environment and maintain accuracy.

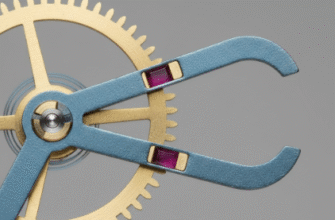

The early demands of underwater science and photography accelerated the necessity for truly waterproof watches. Prior to this, most “water-resistant” cases were only splash-proof. The pressures encountered by Boutan and subsequent photographers forced watchmakers to engineer seals, crown mechanisms, and casebacks that could reliably maintain their integrity against significant hydrostatic pressure, laying the groundwork for the modern dive watch.

Boutan’s need for precise timing was twofold: managing the photochemical process of his plates and, later, ensuring the safety of his brother, Auguste, who assisted him in the cumbersome standard diving dress. The watch, encased and strapped to the wrist or placed within the camera apparatus, became the primary gauge of operational limit.

The Evolution of the Pressure Casing

While Boutan focused on the camera housing, watch manufacturers themselves started to wrestle with the problem of sealing the delicate movements. Hans Wilsdorf, through his company, Rolex, patented the **Oyster case** in 1926, which used a screw-down bezel, caseback, and winding crown. This invention, while not immediately deployed for deep-sea work, was a direct conceptual response to the growing desire for personal timepieces that could survive harsh, damp environments—environments that underwater photographers were pushing into.

The watch worn by Mercedes Gleitze during her 1927 swim across the English Channel, though not a deep-sea dive, dramatically showcased the practicality of the sealed case. This public demonstration cemented the idea that a truly waterproof watch was possible, a vital piece of evidence for the nascent underwater community.

Safety and the Decompression Schedule

As divers went deeper and stayed longer, following the pioneering work of figures like John Scott Haldane on decompression sickness, the role of the watch became entirely linked to survival. Haldane’s decompression tables, published in 1908, dictated that a diver must spend specific amounts of **time** at different depths during ascent to safely off-gas nitrogen from their blood. Without a reliable, easily readable, and entirely waterproof timepiece, adherence to these tables was impossible.

- Exposure Control: The watch was used to time long-duration exposures on film, especially before powerful flash systems became common.

- Bottom Time: It was the sole instrument for measuring total time at depth, which directly determined the required decompression stops.

- Safety Stops: A watch with a rotating bezel (a later, but related, development) allowed divers to track the five-minute safety stop with precision.

From Submersible Viewports to Aqua-Lungs

The American filmmaker and deep-sea adventurer **John Ernest Williamson** took underwater photography to cinematic heights using his ‘Phoenician’ tube in the early 20th century, shooting nature footage and even narrative films from a submerged metal sphere. Although his work used a fixed apparatus, the support divers and the overall operational schedule for the day were entirely governed by precise timekeeping, reinforcing the necessity of reliable marine clocks and watches for any significant sub-surface activity.

The true fusion of the reliable dive watch and underwater photography accelerated after World War II with the popularization of the **Aqua-Lung** by Jacques Cousteau and Émile Gagnan. SCUBA allowed photographers to move freely, bringing their cameras directly to the subjects. The freedom came with an increased personal responsibility for safety. The three primary tools for a mid-century SCUBA diver were the depth gauge, the dive knife, and, most critically, the **waterproof wrist watch**.

The evolution of the dive watch from a simple waterproof case to a specialized instrument with a rotating bezel (used to mark elapsed time) was directly driven by the safety requirements of early underwater photographers and scientists. The failure of a timepiece could mean the missed capture of a rare subject or, more severely, a catastrophic failure to follow life-saving decompression protocols.

Iconic cameras like the Calypso-Phot (later the Nikonos) became ubiquitous, and right alongside them, on the wrist of nearly every prominent underwater pioneer—from Hans Hass documenting the Red Sea to Cousteau exploring shipwrecks—was a purpose-built, highly legible, **robustly sealed timepiece**. The watch was no longer just a timing device for film; it was a non-negotiable component of the life-support system. The visual record we now have of the deep sea—a record born from the dedication of those early photographers—was only possible because they could trust the mechanism strapped to their wrist to accurately count every passing minute beneath the immense pressure.