In the quiet, brightly lit world of a watchmaker’s workshop, a transformation takes place that separates mere time-telling devices from true works of horological art. It is a process of immense skill, patience, and an unwavering pursuit of perfection. We are talking about the intricate craft of hand-beveling and polishing a movement’s main bridge or plate, a technique known in the industry by its French term:

anglage. This is not a step required for a watch to function; it is a declaration of intent, a testament to the human hand’s ability to create beauty in the smallest of spaces.

It all begins with a raw, unadorned component. Fresh from the CNC machine or stamping press, a main bridge is a piece of metal, typically brass, with a utilitarian, matte appearance. Its edges are sharp, functional, and devoid of character. This blank canvas, or

ébauche, holds the potential for brilliance, but it is up to the skilled hands of a finisher, or

angleur, to unlock it. The journey from this industrial state to a gleaming, light-catching sculpture is long and demands absolute precision.

The Art of the File: Creating the Foundation

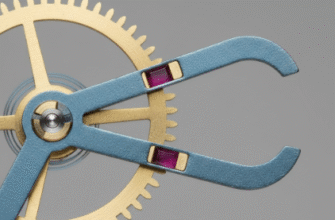

The first and most crucial stage is creating the bevel itself. The goal is to cut a perfectly consistent, 45-degree chamfer along every single edge of the bridge. The watchmaker secures the small, complexly shaped component in a vice or, more traditionally, affixes it to a small wooden peg for better manipulation. The primary tool for this task is a simple, yet unforgiving, hand file.

Starting with a coarser-cut file, the finisher makes careful, deliberate strokes. The pressure must be even, the angle unwavering. One slip, one moment of lapsed concentration, can gouge the surface or create an uneven angle, potentially scrapping the component entirely. The process is repeated, moving to progressively finer files, each one smoothing the surface left by the previous tool. The sound in the workshop changes from a rough rasp to a soft hiss as the metal is slowly shaped. Every curve, every straight line, and every corner must be treated with the same meticulous attention to detail. This initial shaping is the foundation upon which the final mirror polish will be built; any imperfections here will be magnified later on.

The Challenge of the Corners

While straight edges are challenging enough, the true test of an

angleur’s skill lies in the corners. Outward corners must be perfectly sharp, forming a clean point where the two beveled edges meet. However, the pinnacle of the craft is the

inward corner. Creating a sharp, incisive inward angle where two bevels meet is exceptionally difficult. Machines and automated polishing tools tend to round these corners, leaving a tell-tale sign of mass production. A true hand-finished inward corner is painstakingly cut with specialized files and slivers of wood, resulting in a crisp line that is a hallmark of the highest level of watchmaking.

From Satin to Shine: The Polishing Stages

With the bevels perfectly filed, the surface is smooth but still opaque. The next phase involves removing the microscopic scratches left by even the finest files. This is achieved using a series of tools and compounds. Traditionally, watchmakers use slips of wood, such as boxwood or gentian root, charged with abrasive pastes. Starting with a coarser paste, the finisher meticulously works over the beveled surface, following the grain of the filing. The motion is repetitive and requires a sensitive touch to avoid rounding the sharp edges that were so carefully created.

The term black polish, or poli noir, is the ultimate goal of this process. It refers to a surface so perfectly flat and free of imperfections that it reflects light in only one direction. When viewed from any other angle, it absorbs all light and appears completely black, creating a stunning visual contrast with adjacent surfaces.

The process is repeated with finer and finer diamond pastes. The final polishing stage is where the magic truly happens. Using a very hard wood like boxwood and a minute amount of the finest diamond paste, the finisher polishes the bevel until it achieves a flawless, mirror-like shine. This is not simply about making it shiny; it’s about achieving a level of flatness at a microscopic level that is almost perfect. It is at this stage that the coveted black polish emerges, a surface so pristine that it can look like a black hole from one angle and a brilliant flash of light from another.

Why This Herculean Effort?

One might reasonably ask why watchmakers invest dozens of hours into finishing a single component that is often hidden behind a case back. The answer lies in the intersection of tradition, art, and a touch of functionalism. Aesthetically, anglage transforms a functional part into a piece of sculpture. It creates a play of light and shadow within the movement, drawing the eye and highlighting the complexity of the architecture. It is a signature of

haute horlogerie, a clear visual cue that a watch has been crafted with an exceptional level of care.

While primarily for beauty, there is a functional benefit, albeit a minor one. The smooth, beveled edges are less prone to corrosion and are less likely to shed microscopic burrs or metal dust into the delicate workings of the movement over time. Ultimately, however, hand-finishing like anglage is about preserving a legacy of craftsmanship. It is a promise from the manufacturer that no detail is too small, no effort too great, in the quest to create something of lasting value and beauty.