Within the intricate universe of a high-end mechanical watch, there exists a hidden world of artistry and precision that most owners will never see. Beyond the dial and hands lies the movement, a complex city of gears, springs, and levers working in perfect harmony. The structural plates that hold this city together are known as bridges, and their finishing is a critical hallmark that separates true horological craftsmanship from mass production. One of the most vital and visually stunning of these finishing processes is the coating of movement bridges with a whisper-thin layer of rhodium or gold. It is a meticulous practice, a fusion of chemistry and art, performed for two fundamental reasons: unwavering protection and breathtaking beauty.

The journey of a watch bridge from a raw stamped piece of metal to a gleaming component is long and arduous. Typically, these bridges are machined from brass, a reliable and easy-to-work-with alloy. However, brass has a significant weakness: it tarnishes and oxidizes over time, especially when exposed to even minute amounts of moisture or atmospheric contaminants. This corrosion, even on a microscopic level, can generate debris that could interfere with the movement’s delicate pivots and gears, compromising timekeeping accuracy. To prevent this, a protective noble metal coating is applied through an electrochemical process known as electroplating.

The Foundation of Perfection: Surface Preparation

Before a bridge ever sees a plating bath, it undergoes an exhaustive preparation phase. This stage is arguably more critical than the plating itself, as the final coating will mercilessly reveal any and every imperfection on the surface beneath it. The process begins with the complete disassembly of the movement. Each individual bridge is handled with extreme care to avoid scratches or blemishes. The initial step is a thorough cleaning in ultrasonic baths to remove any residual machining oils, dust, or polishing compounds.

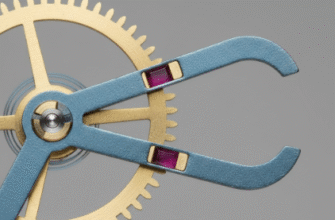

Once immaculately clean, the artistic finishing begins. This is where watchmakers create the decorative patterns that are so prized by enthusiasts. Techniques like

Côtes de Genève (Geneva stripes), with their wave-like parallel lines, or

perlage (circular graining), with its pattern of tiny overlapping circles, are meticulously applied to the brass surface. Every bevel and edge is then chamfered and polished by hand, a process called

anglage, creating sharp, light-catching borders. These decorative finishes are not just for show; they demonstrate a watchmaker’s skill and dedication. Once these patterns are complete, the bridge is cleaned again, passing through multiple chemical baths to ensure it is surgically clean and ready for plating. The quality of the final plated layer is entirely dependent on the perfection of this preparatory work.

The Science of Sheen: The Electroplating Process

Electroplating is a process that uses a direct electric current to deposit a thin layer of one metal onto another. The watch bridge acts as the cathode (the negatively charged electrode) and is submerged in an electrolyte solution, a chemical bath containing dissolved ions of the metal to be plated. A piece of the plating metal, such as pure rhodium or gold, acts as the anode (the positively charged electrode). When the current is switched on, metal ions from the solution are drawn to the negatively charged bridge, where they are reduced to their metallic form and deposit onto the surface, atom by atom, creating a smooth, uniform, and durable coating.

Rhodium: The Cool, White Armor

Rhodium is a rare and precious metal belonging to the platinum group. It is prized in watchmaking for its extreme hardness, exceptional corrosion resistance, and its brilliant, silvery-white luster that is even more reflective than platinum. A rhodium coating provides an incredibly tough protective barrier for the underlying brass. The plating process is highly controlled; the voltage of the electric current, the temperature and chemical composition of the rhodium sulfate bath, and the duration of immersion are all precisely calibrated. Even a few seconds too long or a slight temperature deviation can affect the thickness and appearance of the final coat, which is typically only a few microns thick. The result is a modern, technical, and almost clinical look that enhances the geometric beauty of the movement’s architecture.

The entire electroplating process is incredibly sensitive to contamination. A single speck of dust, a trace of oil from a fingerprint, or an impurity in the chemical bath can ruin the finish completely. This is why watchmakers operate in near-cleanroom conditions. Absolute chemical and environmental purity is not a goal; it is a strict requirement.

Gold: The Warm, Traditional Glow

Gold plating offers the same essential protection against corrosion as rhodium but provides a completely different aesthetic. It imparts a classic, warm, and luxurious feel to the movement. The process is similar to rhodium plating, though the electrolyte solution is typically a potassium gold cyanide bath. Watchmakers can even plate with different shades of gold, such as yellow gold or rose gold. Rose gold, for instance, is achieved by co-depositing a small amount of copper along with the gold, giving the final layer its characteristic warm, pinkish hue. A gold-plated movement often feels more traditional and harks back to the golden age of pocket watches, where such finishing was a clear indicator of a high-quality timepiece.

Final Inspection: The Pursuit of Flawlessness

After emerging from the plating bath, the bridge is not yet finished. It goes through several rinsing stages in deionized water to remove all traces of the electrolyte solution, preventing water spots or chemical residue. It is then carefully dried in a controlled environment. The final and most crucial step is inspection. A watchmaker examines every square millimeter of the bridge under high magnification. They are looking for perfect uniformity in color and texture. There can be no burns, no pits, no dark spots, and no areas where the plating is uneven. The coating must be perfectly adhered to the substrate. Any component that shows even the slightest flaw is rejected, stripped of its coating, and sent back to the very beginning of the process. There is no room for error. This painstaking commitment to perfection is what defines haute horlogerie, ensuring that the hidden heart of the watch is as beautiful and enduring as the face it shows to the world.