Imagine a time when the simple act of washing your hands or getting caught in a sudden downpour could spell doom for your most precious and technologically advanced possession: your wristwatch. For the first few decades of the 20th century, this was the reality. Watches were delicate, intricate machines, and their biggest enemies were not shocks or drops, but the insidious, ever-present threats of dust and water. A single drop of moisture seeping into the case could cause the fine steel components of the movement to rust, while microscopic dust particles could grind the tiny gears to a halt. In this context, the creation of the first truly water-resistant watch case was not just an improvement; it was a revolution, a technical miracle that fundamentally changed our relationship with timekeeping.

The Achilles’ Heel of a Timepiece

To appreciate the magnitude of this achievement, one must first understand the immense challenge. A watch case is not a solid, sealed box. It has multiple points of entry that are essential for its function. Sealing these openings while maintaining their usability was a puzzle that vexed the world’s finest engineers and watchmakers for years. The primary culprits were three key areas: the winding crown, the case back, and the crystal.

The Problem with the Crown

The winding crown was, by far, the most significant obstacle. It is the primary interface for the user, allowing them to wind the mainspring and set the time. This means its stem must pass directly through the case wall and connect with the delicate inner workings of the movement. How could you create a seal around a part that needed to be pulled out, pushed in, and rotated daily? Early attempts involved simple felt or cork gaskets, but these would wear out quickly, lose their sealing properties, and offered minimal protection against anything more than a light splash. It was a gaping hole in the watch’s armor, an open invitation for destructive elements.

The Case Back and Crystal Conundrum

The case back presented another challenge. It needed to be removable to allow watchmakers access to the movement for servicing and repairs. Most early wristwatches used snap-on case backs. While easy to open, they provided a very poor seal that could easily be compromised by a slight knock or the natural flexing of the case on the wrist. Similarly, the crystal, the transparent cover protecting the dial, was typically just pressed into the bezel. This friction fit was far from airtight or watertight. Changes in temperature or pressure could cause it to expand or contract, creating microscopic gaps for moisture and dust to enter. Sealing a watch was like trying to waterproof a house with the doors and windows left slightly ajar.

The Dawn of the Oyster

While several watchmakers experimented with solutions, such as placing a standard watch inside a secondary, sealed outer casing, these were clumsy and impractical. The true breakthrough came in 1926 from a brand that would become synonymous with robust, reliable timepieces: Rolex. Hans Wilsdorf, the visionary founder of Rolex, understood that for the wristwatch to truly succeed, it had to be dependable enough for everyday life. He tasked his engineers with creating a case that was completely impervious to the elements. The result was the legendary

Rolex Oyster case, a design so effective that its core principles are still used in virtually all water-resistant watches today.

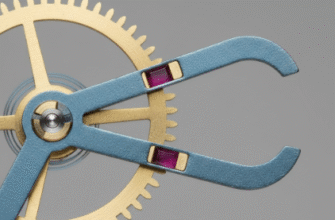

The genius of the Oyster case lay in its systematic approach to sealing every vulnerability. Instead of a simple snap-on back, Rolex engineered a finely threaded case back that screwed down tightly against the middle case, compressing a gasket to create an airtight seal. The bezel holding the crystal was also screwed down, ensuring the crystal was sealed with equal force. But the masterstroke was the invention of the

screw-down winding crown. Rolex patented a system where the crown, after being used to wind or set the watch, could be screwed down onto a threaded tube on the case. This action compressed gaskets inside the crown against the tube, effectively sealing the most vulnerable point of entry, much like a submarine hatch.

To prove the revolutionary nature of the Oyster case, Hans Wilsdorf orchestrated one of the most brilliant marketing stunts in history. In 1927, he gave a Rolex Oyster to a young English swimmer named Mercedes Gleitze as she attempted to swim the English Channel. After more than 10 hours in the frigid, salty water, Gleitze did not complete the swim, but the watch emerged in perfect working order. This public demonstration provided undeniable proof that the Oyster case worked, transforming the perception of the wristwatch overnight.

Why It Was a Miracle

The term ‘miracle’ is not an exaggeration when viewed through the lens of the 1920s. The level of precision machining required to create these threaded components and reliable seals on such a miniature scale was unprecedented. It was one thing to seal a large submarine hatch, but quite another to achieve the same hermetic seal on an object that sits on your wrist. It was a marvel of micro-engineering.

The impact was immediate and profound. Suddenly, a watch was no longer a fragile instrument to be guarded and protected. It became a reliable tool that could accompany its owner anywhere, from the boardroom to the beach. For explorers, divers, pilots, and soldiers, this was a game-changer. They could now rely on their timepieces in the most demanding environments on Earth. The water-resistant case didn’t just protect the watch; it liberated the wearer. It marked the transition of the wristwatch from a piece of jewelry to an essential piece of everyday equipment, a trusted companion for a life of activity and adventure. This single innovation laid the foundation for every dive watch, field watch, and sports watch that would follow, forever changing the course of horological history.